Social-ecological systems and complexity

I always believed nature and people are not separate and know that we need to come up with innovative solutions to create a better future for ourselves and the planet, especially amidst the climate crisis. The social-ecological and complex adaptive systems perspectives (which I just started to delve into) give me such a helpful framework to organise thoughts and look at problems openly.

But then as Paul Cilliers reminds us: “Some hope that a general theory of complexity will provide a new master model for solving all the remaining great problems. Others argue that, instead of delivering grand solutions, the study of complexity opens up our understanding by showing us why it is difficult to model and understand complex systems – an approach that is concerned with the limits of our understanding ... This second, more critical approach to the study of complexity should not be seen as negative. Considering the limits imposed by complexity may be the responsible way to engage with the world. Disregarding these limits can lead to the illusion of neutrality or objectivity.”

Protected areas as social-ecological systems

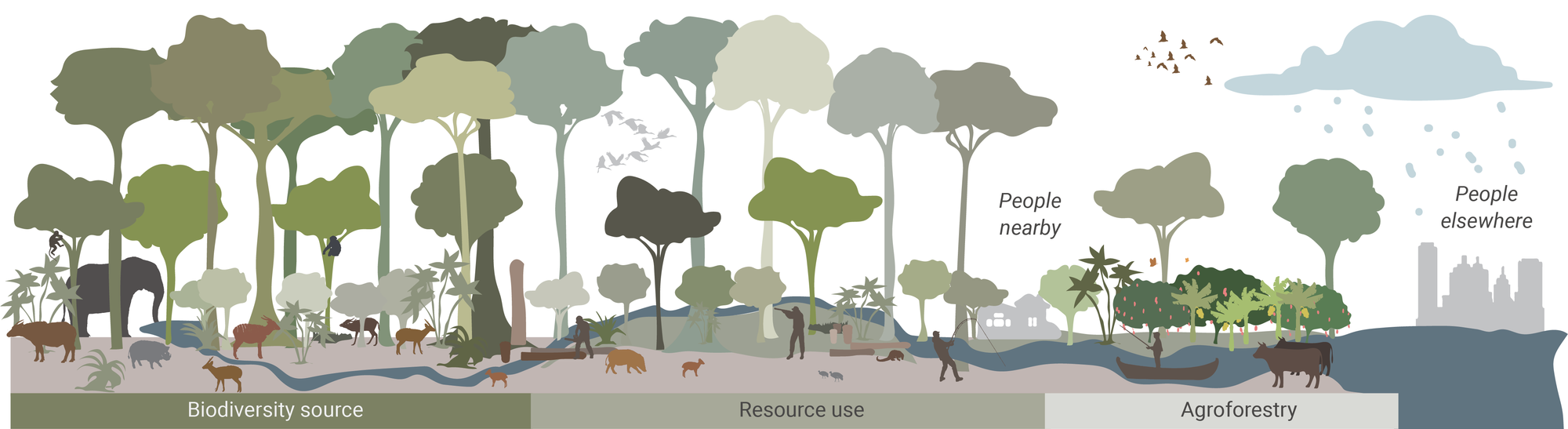

Historically, protected areas were created to mostly conserve iconic landscapes and wildlife, but evolved to also focus on more social aspects such as community livelihoods, economies, fishery replenishment and climate change mitigation. Perhaps today, the ultimate protected area conserves biodiversity, while improving livelihoods of people as illustrated below.

In the example, the biodiversity source focuses on conserving biodiversity, allowing ecological and evolutionary processes to unfold resulting in an overflow of quality resources such as water, meat and wood for people nearby. It can possibly further flow into a more agroforestry-focused area offering sustainable grazing lands and well-pollinated crops. Such a system may also offer materials and carbon sequestration services to people elsewhere.

Bottom-up transformations

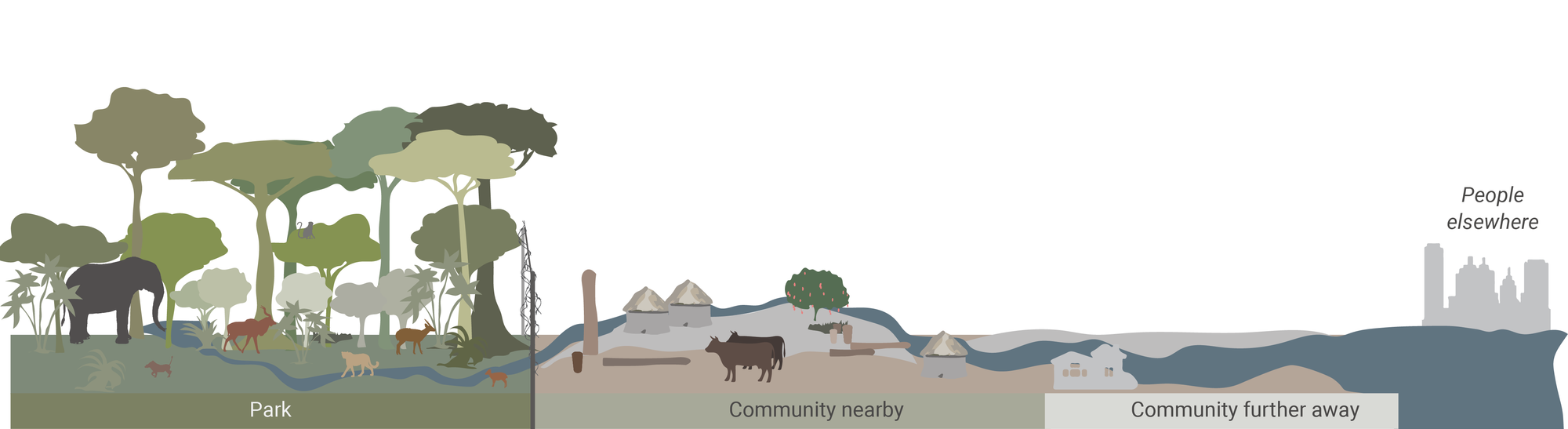

Resilient systems, as the one above, needs active work and the reality (at least for many protected areas in Africa) looks rather like the figure below:

Such systems will not only require innovative home-grown solutions to solve complex problems at different scales but also long-term collaborative work creating examples that others can follow. Perhaps the system above can be transformed into a more resilient social-ecological system like this one:

Let's keep going

I'll continue to explore these two intertwined questions “How can we conserve biodiversity, but not at the cost of people?” and “How can we improve people's livelihoods, not at the cost of biodiversity?”